The recent history of the River Club is instructive

Our last post referred to an observation made by Heritage Western about the River Club HIA, where it referred to the River Club’s “origins in the 1920s.” HWC was critical of this emphasis on recent history. But let’s examine the recent history of the site over the past 100 years because it is instructive to understanding why this development is a continuation of spatial injustice under apartheid. For this, we are fortunate to have sources such as a Baseline Heritage Study of the Two Rivers Urban Park and its supplementary report from 2016 and 2017, respectively, as well as information in other public sources, including the developer’s own HIA report.

The River Club lies on land appropriated by the first Colonial settlers and subsequently owned by the South African Railways at the start of the 20th Century. The origin of turning a low-lying floodplain and wetland, unsuited to housing or industrial purposes, into a use as sports fields and recreational facilities can be traced to one of the findings of the Carnegie Commission of Investigation into the Poor White Problem, 1929-32, that “poor whites” required improved welfare, education and socialization. The issue of extreme poverty among white workers became highly politicized in the mid 1920’s and the early 1930’s. Government attempted to provide employment through large state-run projects and government enterprises such as the railways. This policy imperative increased after the Pact Government in 1924 when the South African Railways became a significant employer of “poor white” workers.

A significant number of skilled and unskilled (white) workers were employed at the Salt River Railway Works in the 1920’s and 1930’s. The Great Depression of 1929 impacted hugely on the economy of South Africa, aggravated by a severe drought which caused a migration of a poor, largely unskilled rural population to the cities including Afrikaans speaking “poor whites”. The South African Government Railways responded (as did other large state employers) with a variety of mechanisms for socialization, involving sport, welfare, nutrition and recreation. Such sports and recreational facilities were set up and run in association with the National Advisory Council for Physical Education.

Because the South African Railways owned substantial tracts of land associated with rail yards and works in the Salt River/Woodstock Area it was able to plan a leisure precinct for its employees. The Railway’s welfare program originated in a pilot welfare scheme devised and run by the Continuation Committee of the National Conference on the Poor White Problem, Kimberley 1934, or the Volkskongres. It was headed initially by the sociologist Dr Hendrik Verwoerd (later Prime Minister), and thereafter effectively by Dr G. Cronje.

The welfare programme in the Liesbeek River Valley was therefore part of a general initiative to provide poverty-stricken and socially depressed white workers with healthy social outlets and improve their quality of life. For Black South Africans, however, there was no such support but rather increasingly discriminatory legislative enactments which supplemented the Native (Urban Areas) Act of 1923. While the fields and club facilities were for the exclusive use of white railway workers, black workers were pushed further to the periphery and the historical attachment of Khoi to the riverine valley rendered invisible.

By the time the Nationalists came to power in South Africa in 1948, the River Club had become a feature of a social system designed to provide leisure opportunities to white workers and a solution to the ‘poor white’ problem, whilst negating any connections of indigenous peoples to the land, a characteristic tenet of apartheid philosophy.

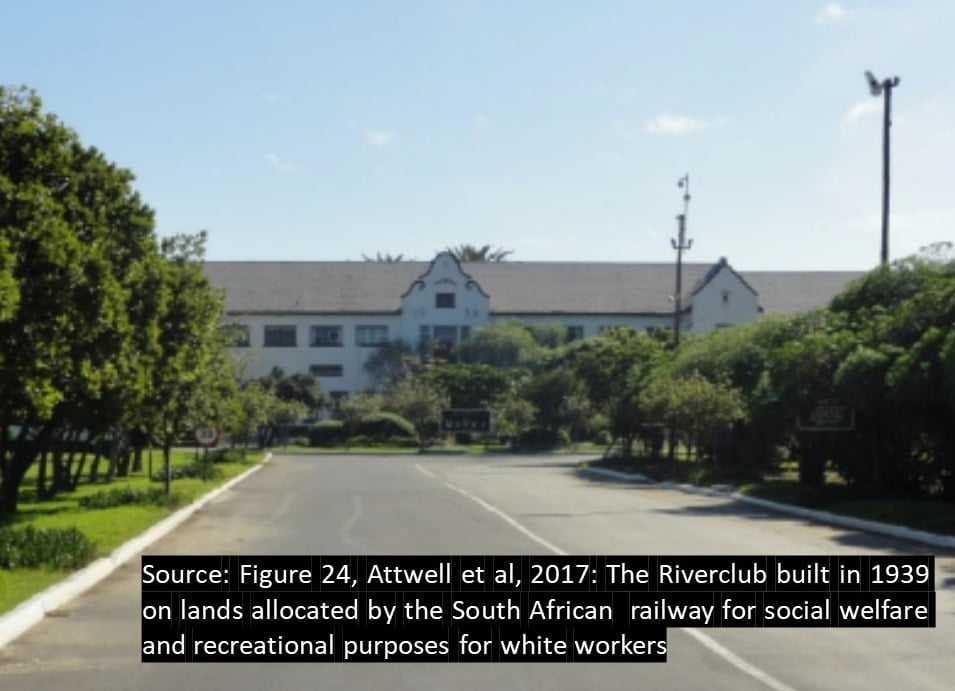

The main buildings of the River Club were completed in 1939 a few years after the development of the recreational fields at the site and provided the nexus for the recreational activities over the next four decades. The Erf was registered in the name of the South African Rail Commuter Corporation Limited and subsequently vested in Transnet Limited by virtue of the Legal Succession to South African Transport Services Act 9/1989 whose property was ceded and transferred to Transnet SOC Limited in June 1993 in the deeds office.

However, by the 1980’s, with Transnet moving most of its activities to Bellville, the patronage of club declined and a series of different tenants failed to maintain the property. The entity known as the River Club was then established in 1993 by the Liesbeek Leisure Property (LLP) (Pty) Ltd on the basis of a long-term development lease (of 75 years). Investment in the property created a well-patronised local venue with restaurant, conference facilities, bar, driving range, and mashie golf course developed in 2002.

The facility continued to operate on land zoned as Open Space owned by South African Railways in its various corporate incarnations until 19th May 2015, when Transnet elected to sell the property. Liesbeek Leisure Properties (LLP) PTY which held the long-term lease exercised its right of first refusal (as long-term tenant) and purchased the property for R 12 million plus VAT. Strangely, Transnet sold the bare dominium, not to a third party but to the lease holder. LLP PTY then sold on the property to Liesbeek Leisure Property Trust (LLPT) within a few months but at a price 8 times higher, being R 100 million. The purchase by LLPT was possible with a bond issued by Investec. The land, then zoned as Private Open Space, which permitted consent uses for recreational purposes, was still designated as unsuited for housing or Mixed-Use development, because it lay in a flood plain and had important heritage and environmental significance.

Despite recent statements by City councillors that it would be irresponsible to allow housing in a flood plain, it is this very permission to build for housing and mixed use in a flood plain that was given by the City’s Municipal Planning Tribunal on the 18th September 2020.

One of the arguments which the Municipal Planning Tribunal ignored on the 18th September 2020 was a statement by Ndifuna Ukwazi who argued that considerations of spatial justice are not just about redirecting public and private land to affordable housing, but also to recognise that heritage and restorative justice are also part of spatial justice. It is here, on the banks of a neglected but sacred river that the continued injustices of apartheid spatial planning can be most clearly seen in the fact that white railway workers under apartheid enjoyed subsidised leisure thanks to the apartheid planning of Transnet when they created a holiday resort on the land from which the Khoi peoples were displaced and with which they have a particular spiritual connection. That land, which was sold on to LLP Pty Limited in 2015 without any indigenous people having a look in, has now been handed to a new consortium of elites to build a new Century City and complete the destruction of what was intended by apartheid planners. If anything should have been done to redress the injustice of apartheid spatial, that is the point at which justice should have prevailed.

What exactly is happening now? Not only have the MPT rezoned the land but the City is ceding to LLPT approximately 10ha of land owned by the City to enable their development to proceed. The development will deliver 150 000 square meters of concrete, high-end commercial office buildings and only 4% affordable housing. Khoi heritage will be sequestered in a media and cultural centre located in an 30m high office building and the amphitheatre and herb garden will be overlooked by the Amazon Campus, a gargantuan 44m high behemoth. That is about the height of the giant grain silo in Salt River in the distance to the north-west.

To welcome this development as a victory for the people of Cape Town is hypocritical at best and betrayal of democracy at worst.

The City of Cape Town has recently released a call for people to nominate various iconic liberation struggle sites around the metropole to a list of sites that would comprise a booklet to showcase various iconic liberation struggle sites around the metropole. As we pointed out in our last post, the Two Rivers Urban Park, including the River Club, has not been listed as one of the provisional sites for inclusion by the City. Please don’t let the colonial extinction of the history of the Khoi people in South Africa and their first resistance to colonial oppression continue. You can write to [email protected] to nominate the Two Rivers Urban Park and the River Club for inclusion on the Liberation Route.

If you haven’t already done so, please do so today.